They are all now dead and can never be replaced but at least they got names. Martha, Benjamin and Incas… Booming Ben and Lonesome George. They were endlings, each one the last known member of its species. Their names remind us that we have epic tales to tell of the decline and fall of entire species.

They are all now dead and can never be replaced but at least they got names. Martha, Benjamin and Incas… Booming Ben and Lonesome George. They were endlings, each one the last known member of its species. Their names remind us that we have epic tales to tell of the decline and fall of entire species.

Martha and Incas were the first to fly into my life. It was 1997 and I described and drew them both in a leaflet about extinct birds I produced for a small bird garden in the north of England. Martha’s story is best known. She was the last Passenger Pigeon, a species we reduced in number from billions to zero in just over a hundred years. She died on 1 September 1914 in Cincinnati Zoo but her body resides still in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. Journalist Eric Freedman visited her there for his 2011 article Extinction is Forever. He wrote:

“Martha arrived at the Smithsonian encased in a block of ice for scientific study. There she was mounted and placed on a small branch now fastened to a block of Styrofoam. The Smithsonian custodians paired her with a male passenger pigeon that died in 1873 in Minnesota. They had no connection with each other during life and were mated only for public display, which hadn’t happened for a long time. Nowadays, Martha and her anonymous pseudo-mate spend virtually all their time in a nondescript locker next to one containing birds Theodore Roosevelt had shot, collected, and studied as a boy. Martha’s organs are preserved separately in fluid. I didn’t ask to see them.”

Freedman chose to see Martha’s body rather than visit her death-place in Cincinnati Zoo, but had he gone there he could have killed two birds with one stone. That’s because on 21 February 1918 — four years after Martha died and in the very same cage — Incas expired. He was the last Carolina Parakeet. Another species had gone extinct. Other endlings include the last known Heath Hen. It acquired the name Booming Ben because it spent years calling out in vain for a partner. More recently we lost Lonesome George, a giant tortoise from Pinta Island in the Galápagos archipelago — and, again, the last of his kind.

Freedman has tracked down other endlings over the years. He saw the stuffed body of what its Uzbek owners claim is the last Caspian Tiger. He visited the zoo in Hobart, Tasmania where Benjamin, the last Thylacine — seen in the video above — died in 1933. Freedman explains:

“To some people, these journeys of mine could seem macabre, a weird fascination with avoidable-turned-inevitable large-scale deaths. But, like a cemetery visit to read ancient headstones, there are lessons to be found in these markers to the dead. So I undertake my endling pilgrimages hoping the visits will make the reality of extinction tangible.”

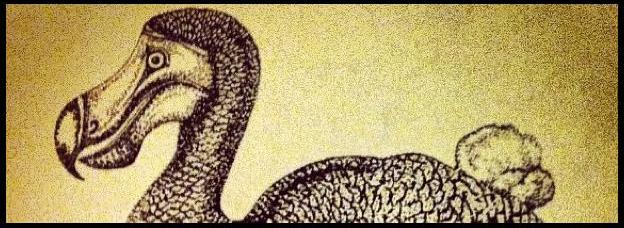

Named endlings are rare. In most species that we have extinguished, the last member was gone before we even noticed. Take the dodo — Raphus cucullatus, among the most famous of all the species we have driven extinct. Here’s one I drew in 1997, a little over 300 years after the last one died.

And here’s how David Quammen imagined that last dodo’s last stand in his brilliant book The Song of the Dodo:

“Raphus cucullatus had become rare unto death. But this one flesh-and-blood individual still lived. Imagine that she was thirty years old, or thirty-five, an ancient age for most sorts of bird but not impossible for a member of such a large-bodied species. She no longer ran, she waddled. Lately she was going blind. Her digestive system was balky. In the dark of an early morning in 1667, say, during a rainstorm, she took cover beneath a cold stone ledge at the base of one of the Black River cliffs. She drew her head down against her body, fluffed her feathers for warmth, squinted in patient misery. She waited. She didn’t know it, nor did anyone else, but she was the only dodo on Earth. When the storm passed, she never opened her eyes. This is extinction.”

“Endling,” wrote science writer Lucas Brouwers last week on Twitter. “A fine, sad word.” He’s right. Sad it may be, but fine it is too. The endlings are creatures upon whose shrugging shoulders we have thrust a kind of nobility. In naming them and in telling their stories, we have made them ambassadors of not only their own species but of all species whose numbers we deplete to the edge of existence and beyond.

Freedman says that when he considers the stories of the endlings, the “abstract becomes personal and allows me to see that these animals’ fates were not inevitable. Their endings had human authorship.” That’s it. We are writing the stories of so many other species. And while stories with endlings don’t have happy endings, they are important tales to tell. They make real our impacts on nature. They remind us that nothing is forever, that one day in some far future there will be a human endling too. What we don’t know yet is how the fate of other species will affect the date of our own departure. There’s a story there to tell.

[Update: 9 May 2013 — Al-Bia Wal-Tanmia (Environment and Development) Magazine in Lebanon has published this Arabic version [PDF] of this article]

I’d never heard of the term “endling” before. Such a sad word and such a tragic doom. Thank you for telling this story.